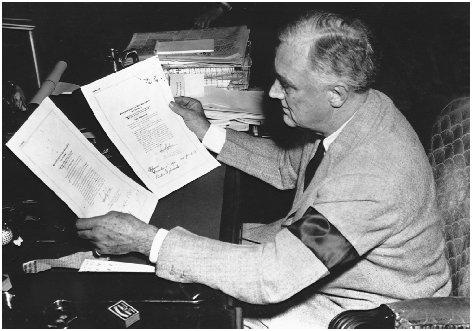

Franklin D. Roosevelt - The shadow of war

A second world war had "come at last," Roosevelt said on hearing the news from Poland. "God help us all." When the war ended, more than five years and 50 million deaths later, the United States would be indisputably the most powerful nation on the ravaged planet. But in 1939, America wavered uncertainly on the periphery of these ominous events.

Roosevelt hoped to preserve the United States from the scourge of war, but he also hoped, from at least 1935 on, to bring the power of his country to bear against the prairie fire of armed aggression that was licking its way around the globe. Three forces constrained him: the lack of political will in his potential allies, Premier Édouard Daladier of France and Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain of Great Britain, cowering in the face of Hitler's bullying; the isolationist mood in America, codified into formal statutes purposely designed to tie the president's hands; and his own uncertainty, both about the means to be employed abroad and about the political risks of frontally challenging the isolationists at home.

Roosevelt did manage to align the United States with the League of Nations sanctions against Italy in the Ethiopian crisis, simply by enforcing the 1935 neutrality law. It prohibited arms shipments to all belligerents, but since Ethiopia could not have afforded to purchase American arms in any event, the real force of the ban fell exclusively on Italy. Similarly, Roosevelt artfully invoked the Neutrality Act during the Spanish civil war, reinforcing the Anglo-French Nonintervention Committee's effort—pusillanimous and myopic though it may have been—to contain the conflict within Spain's borders.

Japan in mid-1937 escalated its six-year-old incursion in Manchuria into a full-scale invasion of China, once again testing Roosevelt's ingenuity in finding ways to check aggression while fettered by the neutrality laws. He responded by refusing to proclaim that a formal state of war existed between the two nations. (Japan officially labeled the conflict an "incident.") He thus forestalled activating the arms embargo and cash-and-carry provisions of the neutrality statutes and preserved China's ability to secure supplies in the United States.

Using isolationist legislation to achieve internationalist ends was a kind of political jujitsu, and the president could employ the tactic only so long. "If Germany invades a country and declares war," Roosevelt explained to a senator in 1939, "we'll be on the side of Hitler by invoking the [neutrality] act. If we could get rid of the arms embargo, it wouldn't be so bad." But the president's efforts to revise the neutrality statutes were repeatedly frustrated by congressional isolationists. Their political power waxed while Roosevelt's waned in the declining days of the New Deal. He called for a "quarantine" against aggression in an eloquent speech in Chicago on 5 October 1937, but still smarting from the lacerations of the Supreme Court reform fight and freshly wounded by the sharp recession then setting in, he failed to capitalize on the generally favorable public response. The foreign press accurately described the quarantine speech as "an attitude without a program." Three months later, isolationists in Congress pointedly reminded Roosevelt of the obstacles confronting an avowedly internationalist program when they mustered 188 votes in the House in favor of a constitutional amendment requiring a national referendum on a declaration of war. Throughout the rest of 1938 and most of 1939, Roosevelt could do little to prepare for the inescapable conflict. Only after the German invasion of Poland did Congress, in November 1939, repeal the mandatory arms embargo. The cash-and-carry provisions of the neutrality laws remained.

Roosevelt moved thereafter to make the United States, as he later described it, "the great arsenal of democracy." Yet he and his countrymen had waited so long to make their weight felt in the scales of diplomacy that the cause they even now so hesitantly joined came perilously close to being lost. After a deceptive lull following his swift conquest of Poland, Hitler unleashed lightning assaults on Denmark and Norway on 9 April 1940. A month later, Germany and Italy invaded France, which crumpled quickly and ingloriously. Jackbooted Fascists now stood astride Europe from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Only Britain, lonely and besieged, stood between them and the United States.

As Hitler's air force pounded Britain in the summer of 1940, the new British prime minister, Winston Churchill, beseeched Roosevelt for aid, especially for destroyers to secure Britain's sea-lanes. Roosevelt had already, in the opening months of 1940, induced Congress to appropriate several billion dollars for defense measures, including an aircraft production program with the then incredible goal of building fifty thousand planes a year. Now, fulminating against isolationists who deluded themselves that the United States could survive as "a lone island in a world dominated by force . . . handcuffed, hungry, and fed through the bars from day to day by the contemptuous, unpitying masters of other continents," he desperately sought ways to bolster beleaguered Britain. In August he hit upon a bold idea: to give Britain fifty American destroyers in exchange for long-term leases on naval bases in the western Atlantic.

With that exchange, Roosevelt inaugurated a collaboration with Churchill that in the history of relations among sovereign states was uniquely intimate and comprehensive. He also risked the wrath of isolationists—and in an election year. While the Battle of Britain raged, Americans waged their own quadrennial political battle to elect a president. Roosevelt, reluctant to relinquish the stage at such a dramatic historical moment, stood for an unprecedented third term. His opponent was Wendell Will-kie, a liberally inclined businessman who had swept out of obscurity to capture the Republican nomination. Fortunately for the cause of American internationalism, Willkie shared much of Roosevelt's appraisal of the international scene and largely refrained from attacking the president's foreign policies. (Roosevelt had earlier taken steps to secure bipartisan cooperation in foreign affairs when in June 1940 he appointed Republicans to head the War and Navy departments.) Roosevelt won by his smallest margin to date, with 27,307,819 popular votes to Willkie's 22,321,018. The electoral tally was 449 to 82. Both houses of Congress remained safely in Democratic hands.

During the campaign, Roosevelt declared that "this country is not going to war." But in the months after the election, events pushed the United States into ever-closer cooperation with Britain and eventually into what amounted to an undeclared naval war against Germany in the Atlantic. Secret talks between British and American military planners in early 1941 established the cardinal principle that in the event of war with both Germany and Japan, the United States and Britain would give priority to defeating Germany. Churchill wrote the president in December 1940, laying out Britain's military plight with sobering candor. To prevail, even to survive, he must have American war matériel and, above all, American money. Roosevelt, still constrained by the cash-and-carry clauses of the neutrality laws, devised another inventive means to meet Britain's needs: the so-called lend-lease program, pledging American goods secured only by a deliberately vague promise of repayment "in kind" at some unspecified later date. Artfully numbered House Resolution 1776, the Lend-Lease Act passed Congress in March 1941. Its enactment marked the effective end of American neutrality and the opening of a floodgate of American largesse through which more than $50 billion in aid was to flow by the war's end.

Lend-lease provided goods and credits principally to Britain and, after Hitler's invasion of the USSR in June 1941, to the Soviet Union as well. But the task remained of delivering the promised matériel safely to British and Russian ports. Wolf packs of German submarines stalking the Atlantic sea-lanes inflicted enormous losses on British shipping. Churchill pleaded for American naval convoys, but Roosevelt balked. He extended American sea and air patrols to Greenland in April and to Iceland in July, but stopped short of authorizing convoys. He at last took that fateful step in August, after a dramatic meeting with Churchill aboard the American cruiser Augusta, off the coast of Newfoundland. There, in Argentia Harbor, the two leaders formulated the Atlantic Charter, a joint statement of war aims affirming their lack of interest in territorial gain and support for self-determination, a liberalized world economic order, and the creation of a permanent international peacekeeping organization. Having thus secured a public declaration of British war aims, Roosevelt was apparently ready for war, though surely not eager for it.

"Everything [is] to be done to force an 'incident' on the Atlantic, Churchill informed his cabinet. The incidents were not long coming. A German submarine fired on the USS Greer off the coast of Iceland on 4 September, and the American destroyer Kearny was torpedoed in the same area a few weeks later. On 30 October the Reuben James sank under German fire, taking more than one hundred American sailors down with it. But before these deliberately provoked incidents could precipitate war in the Atlantic, an unexpected blow in the far-off Pacific in December at last catapulted the United States into the conflict.

Roosevelt had long opposed the Japanese invasion of China, even while the United States paradoxically remained a major supplier of critical war matériel, including aviation fuel, to Japan. Following Hitler's successes in Europe in mid-1940, Japan began to look covetously on the orphaned French and Dutch colonies in the Far East. On 26 July 1940, Roosevelt sought to discourage the Japanese by slapping an embargo on the shipment of aviation gasoline and high-grade scrap metal to Japan. He cinched the economic noose more tightly when Japan signed a pact of military alliance with Germany and Italy in September 1940, and more tightly still when Japanese troops marched into Indochina in July 1941. Jolted by these American moves, Japan made several last-ditch efforts at reconciliation with Washington in late 1941. But Roosevelt, encouraged by Secretary Hull, insisted that Japan withdraw not only from Indochina but also from China, as the precondition for restoring economic relations with the United States. On other matters the Japanese might have been disposed to yield, but on China they were adamant. Diplomacy reached a dead end in late November. Japan now took the fateful step of breaking the deadlock by military means.

American cryptanalysts in late 1940 had cracked the Japanese diplomatic codes, including the top-secret "Purple Cipher." Military leaders therefore knew, as did Roosevelt, that Japan had abandoned diplomacy in early December and was about to strike an armed blow. American forces throughout the Pacific stood on alert. Because the blow was expected to fall in Southeast Asia, Japan scored a devastating surprise when its aircraft swarmed out of the dawn sky over the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on 7 December 1941. Within minutes the Japanese sank or crippled several American warships, killing over twenty-five hundred military personnel and civilians. The next day Roosevelt asked Congress for a declaration of war against Japan. Germany and

Italy declared war on the United States three days later. Roosevelt, so long the hesitant neutral, now faced battle on two fronts.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: