Grover Cleveland - First presidential term

Cleveland gave the country exactly the sort of administration that might have been expected—honest, conservative, and unimaginative. His cabinet was made up of hardworking and public-spirited men who ran their departments efficiently. Thomas F. Ba-yard of Delaware was secretary of state, and Daniel Manning of New York, secretary of the treasury. The other members were William C. Whitney, secretary of the navy; William C. Endicott, secretary of war; Augustus H. Garland, attorney general; William F. Vilas, postmaster general; and L. C. Q. Lamar, secretary of the interior. Lamar, who came from Mississippi, and Garland, a resident of Arkansas, were the first southerners appointed to cabinet posts since the Civil War. As the first Democrat in the White House since the Civil War, Cleveland also appointed many other southerners to lesser federal posts.

The change from Republican to Democratic control of the government meant that Cleveland was subjected to enormous pressures from members of his party seeking government posts. Yet, his campaign promises had encouraged Mugwumps to expect him to expand the scope of the new Pendleton Civil Service Act and refrain from discharging Republicans merely to make places for his own supporters. The president found it impossible to satisfy both points of view, in part because he had no clear idea of how the civil service should be staffed. He announced that no one would be fired without cause and that only properly qualified people would replace those who were discharged. In his usual, conscientious way, he devoted much time to going over the records of applicants and weighing the merits of candidates for both major and minor posts. The task both bored and distressed him. He was soon complaining of "the damned, everlasting clatter for office."

His concept of what it meant to be properly qualified was partisan and (still worse) out of date. "Reasonable intelligence" and a decent grade-school education were the only "credentials to office" that most federal jobs required, he told the head of the Civil Service Commission. He also believed in the old Jacksonian system of rotation in office. Since public service was a privilege and a duty in a democracy, any officeholder might be "rotated" after four years to make room for someone else. Starting with what he called "offensive partisans," which in practice came even to include Republicans whose offense had consisted only of campaigning for Blaine, the administration gradually removed most of the government workers who had not been given job security under the Pendleton Act. Mugwumps and others who had hoped that Cleveland would greatly expand the coverage of the act were bitterly disappointed.

Like the other presidents of the era, Cleveland had a rather narrow view of the scope of presidential authority. "The office of the President is essentially executive in its nature," he said. He did not believe it proper "to meddle" with proposed legislation. "It don't look as though Congress was very well prepared to do anything," Cleveland wrote in December 1885. "If a botch is made at the other end of the Avenue, I don't mean to be a party to it." This attitude was a convenient way to avoid getting involved in politically controversial matters, especially for a Democrat, since the party was made up of many disparate and often antagonistic groups. But in his case the attitude was heartfelt.

He was, nonetheless, perfectly willing to resist congressional actions he disapproved of. Just as he had in Buffalo and Albany, he vetoed bills he disliked with evident relish. He repeatedly rejected private bills and pork-barrel legislation. His most significant action of this sort was probably his veto of the Dependent Pension Bill of 1887, a measure that would have granted pensions even to the needy parents of men who had died while in service.

Although a number of important laws were passed during his term, Cleveland had little to do with most of them other than to add his signature after Congress had acted. These included the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887; the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, which invested Indians with American citizenship and assigned plots of reservation lands to individual, rather than tribal, Indian ownership; and a law of 1889 raising the Department of Agriculture to cabinet status. Cleveland favored these measures but did little to shape them.

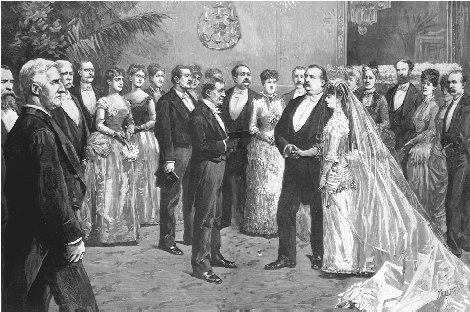

Aside from his attitude toward presidential power, which was common in his day, Cleveland lacked some other qualities that make a good leader. He really did not much enjoy being president, and he found the give-and-take necessary for success in politics positively objectionable He got on badly with reporters, resenting their inquisitiveness and tendency to sensationalize the most trivial events. He was poor at delegating authority. Despite—or perhaps because of—his earlier convivial habits, he was something of a loner in the White House. He had no taste for speechmaking and handshaking, or for crowds, official social gatherings, and the punctilio of receptions. Some of this changed after his marriage in 1886 to Frances Folsom, the daughter of his former law partner. He was forty-nine and the bride only twenty-three, but the marriage proved to be happy and fruitful.

The most difficult issue that Cleveland faced during his first term involved the government's finances and their effect on the condition of the nation's economy. The country was expanding in wealth and population at a rapid rate, but the supply of money in circulation was not keeping up with this growth. The result was a steady and apparently relentless deflation that injured anyone who was in debt, a classification that included large numbers of farmers who worked mortgaged land, often with machinery purchased with borrowed money. To deal with this problem, Congress passed the Bland-Allison Act of 1878, which increased the amount of money in circulation by purchasing and coining large amounts of silver. Many conservatives, Cleveland among them, feared that "inflating" the currency in this manner would so frighten investors and businessmen that it would cause a depression.

Cleveland proposed to deal with the problem by ending government purchases of silver and reducing tariffs on foreign goods. Lower duties would mean lower prices for consumers and would reduce the embarrassing surplus that had accumulated in the treasury, which was a further drain on the amount of currency in circulation. When Congress failed to act on the tariff, Cleveland decided to force the issue. He summoned what became known as the Oak View Conference, a series of meetings with Democratic congressional leaders at Oak View, his summer residence outside Washington. At these meetings he persuaded the congressmen to draft an effective tariff-reduction bill. Then he took an unprecedented step: he devoted his entire annual message to Congress on 6 December 1887 to a call for tariff reduction. The current rates were a "vicious, inequitable,

and illogical source of unnecessary taxation." Protected by these high duties, manufacturers were making "immense" profits. If the duties were lowered, "the necessaries of life used and consumed by all the people . . . should be greatly cheapened."

Normally the annual messages to Congress required of presidents by the Constitution were routine summaries of the activities of the various departments and grab bags from which the legislators might draw suggestions for future actions. By centering on one important issue, Cleveland focused national attention on that issue.

Unfortunately he failed to follow up on this dramatic step. In July 1888, Roger Q. Mills of Texas, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, introduced a bill removing the duties on raw wool, lumber, salt, copper ore, tinplate, and several other products, and reducing the duties on such important items as iron and steel, sugar, and woolen cloth. But Cleveland did nothing to press the issue after the bill was introduced. He did not use his influence with congressmen. He refused even to make speeches on the subject or to issue further statements explaining what he thought should be done. The Mills bill passed the House of Representatives but was defeated in the Senate. The tariff question therefore became the main issue in the presidential election of 1888.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: