The Second Term

Bernard A. Weisberger

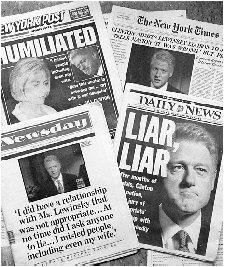

It has traditionally been the case that twice-elected presidents, no matter how successful their first term, have rocky rides in the second. Even George Washington suffered editorial denunciations after 1796. Jefferson left office amid the wreckage of his despised Embargo Act (1807). Jackson was officially censured by the Senate after being reelected in 1832. Franklin D. Roosevelt suffered major political setbacks in 1937 and 1938 and conceivably would not have won—or even been a candidate for—a third term had war not broken out in 1939. Nixon had Watergate and Ronald Reagan Iran-Contra. Bill Clinton managed to extend and exceed the pattern with the Monica Lewinsky scandal. It resulted in his becoming the first duly elected president in U.S. history to be impeached, tried, and acquitted by the Senate (Andrew Johnson, impeached in 1868, had been elected vice president and succeeded Lincoln after his death). It was a distinction that the man from Hope, however eager to leave his mark on history, could hardly have enjoyed.

The Lewinsky scandal, which took more than a year to play out its course, dominated and overshadowed other aspects of Clinton's lame-duck turn on the national stage. In itself a sordid tale of lust, weakness, and arrogance on his part, and of political malice and vindictiveness on that of his accusers, it nonetheless raised serious questions about the meaning of the impeachment clause of the Constitution, the possible political abuse of the process, and the future course of congressional-presidential relations. These were left unanswered by the president's ambiguous victory. The problem for a historian of the episode is in separating the weighty political and cultural issues at its core from the mass of surrounding sleaze. One other serious aspect of the event is its reawakening of the always fascinating question of how the private character of a chief executive affects his role as a national leader. Can anything be learned about the Clinton administration as a whole from the astonishing contrast between the intelligent, politically sensitive, and skillful Bill Clinton of two winning presidential campaigns, and the Bill Clinton who risked his family and the career he had spent a lifetime

building for short-lived sexual gratification? That, too, remains an open question.

The one certainty is that the impeachment fitted into the defeat-and-comeback pattern that had marked Clinton's rise to the top. The House vote that placed him on trial for his political life before the Senate took place only two years and one month after his 1996 reelection, which itself followed by just two years the humiliation of having the Democrats lose control of the Congress on his watch. And in the fall of 2000, only eighteen months after his acquittal, his standing in popularity polls was so high that had there been no constitutional amendment prohibiting it, he might well have run successfully for a third term.

There are no simple explanations with Clinton. But clearly, his interludes of success owed much to his flexibility, persuasiveness, and good luck in holding office in relatively prosperous and peaceful times. The first year of the second term gave evidence of all three.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The following books were essential to the writing of the essay detailing Clinton's first term: Elizabeth Drew, On the Edge: The Clinton Presidency (New York, 1994), and Showdown: The Struggle Between the Gingrich Congress and the Clinton White House (New York, 1996); Bob Woodward, The Agenda: Inside the Clinton White House (New York, 1994), and The Choice (New York, 1996). David Maraniss, First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton (New York, 1995), and David Maraniss and Michael Weisskopf, "Tell Newt to Shut Up!": Prizewinning Washington Post Journalists Reveal How Reality Gagged the Gingrich Revolution (New York, 1996). Other books that helped frame this essay include E. J. Dionne, Jr., Why Americans Hate Politics (New York, 1991), and They Only Look Dead (New York, 1996). With his presidency incomplete, Clinton's story is still a breaking story, told largely by newspapers. This essay relied on articles from the Washington Post , the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times .

Other valuable sources include James B. Stewart, Blood Sport: The President and His Adversaries (New York, 1996); John Brummet, Highwire (New York, 1994). Phyllis Johnston, Bill Clinton's Public Policy for Arkansas, 1979–1980 , (Little Rock, Ark., 1982); and Ernest Dumas, The Clintons of Arkansas (Fayetteville, Ark., 1993). On the First Lady, see Rex Nelson, The Hillary Factor (New York, 1993); Donnie Radcliffe, Hillary Rodham Clinton (New York, 1993); and Judith Warner, Hillary Clinton: The Inside Story (New York, 1993).

The following books provide an early accounting of the first term: David Halberstam, War in the Time of Peace: Bush, Clinton, and the Generals (New York, 2001); James McGregor Burns, et al., Dead Center: Clinton-Gore Leadership and the Perils of Moderation (New York, 1999); Peter Baker, The Breach: Inside the Impeachment and Trial of William Jefferson Clinton (New York, 2000); Richard A. Posner, An Affair of State (Cambridge, Mass. 2000).

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: