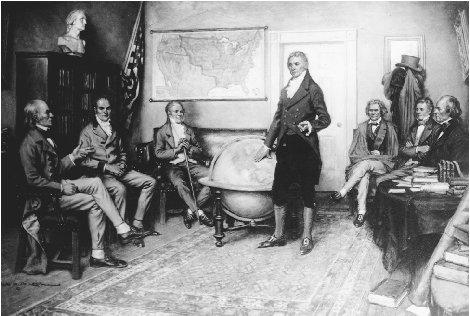

James Monroe - Foundations of the monroe doctrine

Now that the wars precipitated by the French Revolution were over, Monroe had an opportunity to develop foreign policy in new directions. No longer need the executive be preoccupied with the protection of neutral rights and the need to preserve American neutrality. Among Monroe's major objectives, fully supported by Adams, was the recognition of the United States as the only republic of consequence in the world and the strongest power in the Americas. The nation no longer would seek its aims through the patronage of European powers, as Jefferson had relied on France, but would pursue an independent course. Monroe shared the expansionist aims of his generation and with Adams' help fully exploited every opportunity for expanding American territories.

The most immediate problems demanding attention after his inauguration were those arising from the revolutionary movements in Spain's Latin American colonies. Some had been resolved while he was secretary of state, when he had helped formulate a policy of neutrality highly beneficial to the insurgents. Monroe, deeply sympathetic to the revolutionary movements, was determined that the United States should never repeat the policies of the Washington administration during the French Revolution, when the nation had failed to demonstrate its sympathy for the aspirations of peoples seeking to establish republican governments. He did not envisage military involvement but only the provision of moral support. To go beyond this would do the colonies more harm than good, since it would invite European intervention to restore them to Spain. Monroe's caution was justified, for the European powers had intervened in Europe to suppress revolutions in Spain itself and in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Monroe's policy was also shaped by his desire to obtain from Spain the long-sought cession of Florida and a definition of the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase. Premature action in extending recognition

to the former colonies would jeopardize the possibility of a settlement with Spain. Still, recognition had to be considered. In order to obtain more accurate information than that appearing in the press, Monroe, shortly after he entered office, sent a special commission to South America to report on the stability of the newly independent states.

As soon as Adams arrived in October 1817 to take his place in the cabinet, Monroe discussed a more immediate issue than recognition. The various insurgents had freely issued letters of marque to privateers, many of whom were Americans. Behaving more like pirates than privateers, they had made their headquarters on Amelia Island, within the jurisdiction of Spanish Florida. With the approval of his cabinet, Monroe authorized an expedition to occupy the island and end this annoyance.

In December, Monroe took more drastic action, authorizing Andrew Jackson to lead an expedition into Florida to pursue Indians raiding the southern frontier. This invasion was justified by the provision of Pinckney's Treaty of 1795, in which Spain had promised to restrain the Indians living under its jurisdiction. Because Jackson had been specifically instructed not to occupy Spanish posts, his seizure of St. Marks and Pensacola was truly embarrassing for the administration. Moreover, his execution of two British traders after a summary trial on the grounds that they were inciting the Indians threatened to create a major international crisis.

Jackson's conduct created a furor, for it was widely alleged that by his actions he had infringed on the congressional power to declare war. The cabinet was sharply divided on this issue. Calhoun and Crawford were among the many who urged that the general be repudiated, while Adams, sensing that at last Jackson had given the administration the lever needed to pry Florida from Spain, recommended that his conduct be approved.

Sensitive to the constitutional issues and yet unwilling to give Spain an advantage by an outright condemnation of the general, Monroe found a middle course acceptable to the secretaries. In reporting on events in Florida in his annual message, he informed Congress that Jackson had indeed overstepped his orders but had done so on information received during the campaign that made the action necessary. Monroe added that the posts had promptly been restored once Jackson had achieved his objectives. Monroe's position was effective in checking the massive anti-Jackson campaign launched in Congress by states' rightists and those anxious to weaken Jackson's standing as a presidential candidate. Jackson was not pleased with Monroe's formula, which fell short of the positive approval he believed he merited. His sensitivity on this point was a major factor in his breach with Calhoun in 1830.

The congressional debate on the resolutions condemning Jackson were under way at the very time that Adams and the Spanish minister were concluding a treaty for the cession of Florida and the extension of Louisiana's western boundary line northward and westward to the Pacific. The administration's concern that Jackson's execution of British subjects might lead to war proved unfounded. The British, having more important concerns on the Continent, made no protest. When Spain failed to ratify the treaty within the six-month time limit, the president contemplated asking Congress in his annual message of 1819 for immediate authority to occupy Florida. However, after he learned that France and Britain were exerting pressure on Spain to ratify, he requested instead contingent authority, suspending action until the arrival of a special emissary from Spain. Although Clay and other advocates of immediate recognition of the new Latin American states were critical of Monroe's delay, they were too much absorbed in the Missouri debates to raise serious objections in Congress.

Spain ratified the treaty late in 1820, but Monroe still held back from immediate recognition of the new Latin American regimes because of doubts about their stability. Not until March 1822 did he inform Congress that permanent governments had been established in the United Provinces of La Plata (present-day Argentina), Chile, Peru, Colombia, and Mexico. He requested an appropriation for diplomatic missions to these nations.

Adams' instructions for the new ministers, drafted under Monroe's careful supervision, declared that the policy of the United States was to uphold republican institutions and to seek treaties of commerce on a most-favored-nation basis. The new diplomats were also instructed to let it be known that the United States would support inter-American congresses dedicated to the development of economic and political institutions fundamentally differing from those prevailing in Europe. The articulation of an "American system" distinct from that of Europe was a basic tenet of Monroe's policy toward Latin America. Monroe took pride in the fact that the United States was the first nation to extend recognition and to set an example to the rest of the world for its support of the "cause of liberty and humanity."

Monroe was aware that recognition did not provide an effective shield against foreign intervention to restore Spain's colonies. This threat became an immediate concern in October 1823 when dispatches arrived from Richard Rush, the minister in London, informing the president that Foreign Secretary George Canning was proposing that the United States and Great Britain jointly declare their opposition to European intervention. This astounding proposal from so recent an enemy was given the closest consideration.

Monroe at once wrote Madison and Jefferson, who both urged him to accept. In spite of their endorsement, Monroe had serious doubts. To accept the British proposal would make the nation once again seem subordinate to a European power and would not enhance American prestige among Spain's former colonies. Acceptance would also involve a declaration repudiating further territorial expansion at Spain's expense and thus rule out the prospect of acquiring Cuba, an event Adams and many others thought most likely. Monroe also sensed that the people were not yet ready for such close cooperation with Great Britain.

Monroe explored the proposal in detail with his secretaries at lengthy cabinet meetings in November 1823. (Crawford, then seriously ill, was absent.) All agreed that joint action was neither possible nor essential, since the British cabinet had obviously already decided on its policy. At first Monroe felt that a circular diplomatic note would be sufficient to state American opposition to intervention. This had the disadvantage that as a private communication it would not be publicized.

It was the president who hit on the means of announcing the American position to the world: he would include a general statement in his annual message of 2 December 1823. Putting forward the principle that "the political system of the allied powers is essentially different . . . from that of America," he announced that the United States would view any interference in the internal affairs of the American states as an "unfriendly" act. He coupled this with the statement that the United States itself adhered to a policy of noninterference in the internal affairs of other nations. A third principle, the work of Secretary Adams, concerned Russian expansion on the West Coast and declared that the United States considered the Americas closed to European colonization.

A few days after Monroe delivered his message, the American press reported that a large expedition destined for South America was being collected at Cádiz. This report, which later proved erroneous, led Monroe to review the position of the administration and to inform Rush that the United States would undertake further discussions with the British on the possibility of cooperation, should intervention take place. This did not mean, as he explained in a private letter to Rush, that he was committing the nation to "engage in war." What Monroe did not know in December 1823 was that the threat of intervention had vanished in the face of the express opposition of the British government. (In the early twentieth century President Theodore Roosevelt and his successors employed the Monroe Doctrine to justify American intervention in the internal affairs of Latin American states—an interpretation never intended by its author.)

The rejection of the British proposal in regard to Spain's colonies did not mean that Monroe was averse to joint action that did not make the nation seem to be playing a subordinate role. Since the end of the War of 1812 there had been tentative moves by Great Britain toward a rapprochement. The Great Lakes had been demilitarized by the Rush-Bagot Agreement in 1817, and the following year American negotiators had obtained a concession on the fisheries as well as an agreement compensating Americans for slaves removed by British forces at the end of the war. Efforts to obtain concessions for American trade in the British West Indies had been repeatedly rejected.

A more hopeful step was undertaken in the summer of 1823 when Monroe and Adams negotiated an agreement to establish an international patrol to suppress the slave trade. Monroe had rejected the initial proposal in 1819 because it would have required the United States to abandon its position on neutral rights by permitting British ships to stop and search American ships on the high seas. This objection was apparently lessened in 1822 when the House, yielding to the pressure of the American Anti-Slavery Society, adopted a resolution condemning the slave trade as piracy. Since pirates could not claim the protection of any national flag, suspect ships could be stopped and searched by the international patrol established by the British. Congressman Charles Fenton Mercer, a friend and neighbor of the president's, had been the principal agent in securing the adoption of the resolution. Acting on this basis, Monroe, who had long sought to open the way to a rapprochement with Great Britain, was prepared to make a major change in American policy on neutral rights and participate in the international patrol, a measure long urged by the British. In 1823 an agreement to this effect was negotiated with the approval of all the cabinet except Adams, who suspected (correctly) that he would be blamed for what many would regard as a sacrifice of a basic American right.

The Senate ratified the treaty early in 1824 with such crippling amendments that the British government withdrew its ratification. The opposition was directed by supporters of Crawford seeking to damage Adams' presidential ambitions. Monroe was deeply offended, since Crawford had been one of the most ardent advocates of the proposal. Crawford was too ill to have actively directed the maneuvering against the treaty, but it was not the first instance that Monroe felt that the secretary of the treasury had been disloyal. The year before, Monroe had seriously considered dismissing Crawford from the cabinet but held back, realizing that it would simply exacerbate political rivalries.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: