Martin Van Buren - Administration and cabinet

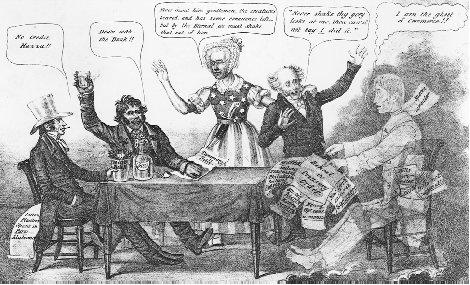

Van Buren hoped that his cabinet appointments would stop Whig momentum in the South and restore confidence in the Democrats as a party of sectional unity, but a legacy of administrative turbulence limited Van Buren's freedom of choice. Indeed, Andrew Jackson had never managed to create a workable relationship with his formal cabinet. During Jackson's first year in office, cabinet factionalism had proved so disruptive that the president ceased formal meetings. He turned instead to a coterie of western advisers, prompting opponents to brand this group a "kitchen cabinet" and charge the president with violating constitutional customs. The president continued to rely on informal advice but resumed regular cabinet meetings in 1831, if only to silence his critics. While Van Buren intended to restore the cabinet to its rightful place in the executive branch, he could not appoint men of his own choosing without removing Jackson's appointees, thereby deepening suspicions of Democratic instability.

As a former secretary of state, Van Buren realized the importance of this premier cabinet post. Georgia's John Forsyth was the last of Jackson's four secretaries of state. A staunch presidential supporter during the nullification crisis, Forsyth had served in both the House and the Senate. Although he decided to retain Forsyth, Van Buren was suspicious of the Georgian's political orthodoxy. The president-elect received numerous letters urging appointment of another southerner to the cabinet to redress Jackson's long neglect. Van Buren tried to satisfy this demand by asking Virginia's senator William C. Rives, disappointed aspirant for the Democratic vice presidential nomination in 1835, to head the vacant War Department. Maintaining that only the State Department interested him, Rives declined and thus made an open break with Van Buren that would have a significant impact on relations with Congress.

Rather than offend Rives further by turning to another Virginian, Van Buren convinced South Carolina's Joel Poinsett to become secretary of war. Whatever gain Van Buren made by adding a second southerner was offset by Poinsett's political views. Like Forsyth, the native of Charleston had been a strong supporter of Jackson's nullification policies.

The retention of Jackson's secretary of the treasury, Levi Woodbury, and postmaster general, Amos Kendall, preserved a sense of continuity and sectional balance, which Van Buren considered essential for party cohesion. New Hampshire's Woodbury had been a cabinet member since 1831, initially as secretary of the navy. Although friendly to Van Buren, he leaned toward the hard-money policies that had become dominant in the last year of Jackson's' presidency. Kentucky's Kendall represented the West and had been the most powerful of Jackson's cabinet members. A skilled political journalist, he had been a key member of the Kitchen Cabinet and instrumental in directing the attack on the bank. Appointed postmaster general in 1834, Kendall had remained fiercely loyal to Jackson and openly suspicious of Van Buren. Like Woodbury, Kendall expected to maintain his status as a member of the inner circle and architect of both fiscal and political strategy.

Van Buren exerted more personal control over the two remaining cabinet posts. He convinced his friend and former law partner, Benjamin F. Butler, to continue as attorney general, a post Butler had accepted at Van Buren's urging in 1833. Van Buren was well aware that Butler felt uncomfortable in Washington and longed to return to Albany. The resignation of a former member of the Albany Regency at the outset of his administration would have embarrassed Van Buren and fed rumors of serious Democratic dissension. While succeeding in his entreaties with Butler, Van Buren failed in his efforts to convince Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson to retire to

a diplomatic post in Belgium. Van Buren would have preferred to replace the sixty-six-year-old New Jerseyite with a younger man.

Despite the political pressures created by the Panic of 1837, Van Buren managed to restore the cabinet's traditional role. He continued weekly meetings and discontinued the informal gatherings of advisers that had attracted so much attention during Jackson's presidency. Van Buren solicited advice from department heads, especially during times of domestic and foreign turmoil. In such emergencies, the cabinet met daily. Van Buren tolerated open and even frank exchanges between cabinet members, perceiving himself as "a mediator, and to some extent an umpire between the conflicting opinions" of his counselors. Such detachment allowed the president to reserve judgment and protect his own prerogative for making final decisions. These open discussions gave cabinet members a sense of participation and made them feel part of a functioning entity, rather than isolated executive agents. Always an astute politician, Van Buren realized that the cabinet could communicate official decisions to the states and work to ensure party cohesion.

In his efforts to restore party harmony, Van Buren worked closely with key Democrats in Congress, where divisiveness had reached alarming proportions during the nullification crisis. New York's Churchill Cambreleng, chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee and long an intimate friend, took an active role in fashioning legislation to respond to the Panic of 1837. Van Buren's protégé Silas Wright performed similar duties in the Senate, where he chaired the Finance Committee and was floor manager for Democratic legislation. Cambreleng and Wright were extremely effective leaders. A study of congressional voting behavior in the first two sessions of Congress during Van Buren's administration shows a partisan coherence in both houses of better than 85 percent. Van Buren rarely quarreled with the Senate over appointments, unlike his predecessor. Having assembled a compatible cabinet and a group of advisers with control in Congress, Van Buren looked forward to a cessation of the open political warfare of the past decade.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: