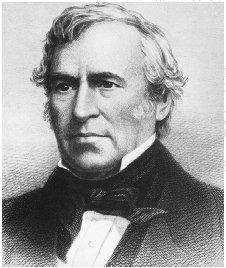

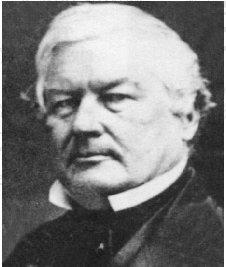

Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore

Norman A. Graebner

ZACHARY TAYLOR entered the world of politics fresh from his personal triumphs in the Mexican War. Leaders of the Whig party had condemned the war as an inexcusable aggression against Mexico, but they recognized in Taylor's unassuming manner and immense popularity qualities that would make him an ideal presidential candidate to recapture the White House after four years of James K. Polk. The Whigs, no less than the Democrats, had principles, but many wondered whether Taylor, whose entire career had been in the army, either understood or accepted them.

In April 1848, while Taylor was still saying that he was a no-party candidate, several southern friends prepared a letter that he copied and sent to his brother-in-law, Captain John S. Allison. In it Taylor acknowledged that he was not sufficiently familiar with public issues to pass judgment on them. He wrote, "I reiterate . . . I am a Whig but not ultra Whig.. . . If elected I would not be the mere president of a party—I would endeavor to act independent of party domination, & should feel bound to administer the Government untrammelled by party schemes."

Taylor believed that Congress, not the president, should have complete control of the major issues before the country. The Allison letter was sufficiently Whig in doctrine to assure Taylor's fourth-ballot nomination at Philadelphia in June 1848. Not all Whigs were pleased. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune , termed the convention "a slaughterhouse of Whig principles." To balance the ticket, the convention named Millard Fillmore, an old-line Whig from New York, for the vice presidency. The convention adopted no platform.

Whig leaders sought to capitalize on Taylor's stature as a national hero and his broad appeal to Americans everywhere. Still Taylor was a man of the South, born in Virginia (24 November 1784) and raised in Kentucky in an aristocratic slaveholding family. A slaveholder himself at the age of thirty, he soon extended his planting operations into Louisiana and Mississippi. Despite a series of misfortunes caused by invalid land titles, falling cotton prices, bollworms, cutworms, and flooding, he managed by 1847 to enter the select company of planters who owned more than a hundred slaves. But Taylor was not ostentatious. He was of average height, muscular, and heavy-boned. His clothing was ordinary, often ill fitting. He had a temper and sometimes displayed it, but generally he conducted himself with unstudied ease, displaying simple good manners. His personal and family life was untouched by scandal. Despite his apparent wealth, Taylor lived modestly at his cottage in Baton Rouge or at his Mississippi plantation, Cypress Grove.

Political success in 1848 lay in the ability to neutralize a divisive sectional issue already tormenting the nation's politics. Polk had decreed that the Mexican War would bring California and New Mexico into the Union, and the annexation of Texas in December 1845 as a slave state had conditioned the antislavery forces of the North against the further extension of slavery into newly acquired territories. In August 1846, David Wilmot of Pennsylvania moved to amend an administration request for $2 million to aid in negotiating a peace with Mexico by adding the proviso that "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude" should ever exist in any territory acquired from Mexico "except for crime, whereof the party shall first be duly convicted." Northern majorities carried the Wilmot Proviso through the House; Democratic managers kept the antislavery measure off the Senate floor. South Carolina's John C. Calhoun met the sectional challenge in February 1847 with the argument that all states had equal rights in the territories, including the right of importing slaves into them. Congress, as the agent of the states, had no right to legislate slavery into or out of the territories. To prevent a serious disruption of their party, Democratic leaders bent on expansion searched for a compromise. Polk and Secretary of State James Buchanan favored the extension of the Missouri Compromise line of 36°30' to the Pacific, but Lewis Cass of Michigan, leader of the administration forces in the Senate, produced the celebrated alternative of "popular sovereignty." Cass's plan would permit people of all sections to move freely into any new territory. When that region had sufficient population to warrant a territorial legislature, that legislature would decide the question of slavery in the territory.

Popular sovereignty became the official position of moderate Democrats everywhere, especially in the North and West. Proslavery spokesmen of the South saw immediately that popular sovereignty assured southerners no greater access to the territories than would the Wilmot Proviso. Cass's doctrine, charged the Charleston Mercury in January 1848, would merely transfer political control of the territories from northern congressional majorities to "mongrel" territorial populations consisting largely of northerners. In mid-January, D. L. Yulee of Florida introduced a resolution in the Senate declaring that neither Congress nor a territorial legislature had the constitutional right to exclude slavery from any territory of the United States. William L. Yancey of Alabama carried these southern demands into the Democratic convention that gathered in Baltimore in May. When the Democrats nominated Cass for the presidency, northern proviso Democrats bolted the party and, joined by rebellious Whigs who distrusted Taylor, held a convention at Buffalo in August, formed the Free-Soil party, and nominated Martin Van Buren for the presidency.

Throughout the campaign Taylor's doubtful allegiance to Whig principles troubled party leaders, especially when he accepted a local Democratic nomination. Thurlow Weed, the powerful Whig boss of New York, threatened to call a mass meeting to denounce the party's candidate. Fillmore suggested rather that he and Weed address a letter to Taylor. Taylor replied on 4 September in the form of another Allison letter in which he again defined his principles as Whig. This held the party in line.

Taylor's final victory was modest, with 1,360,000 popular votes to 1,220,000 for Cass and 291,000 for Van Buren. Taylor's margin in the electoral college was more decisive (163–127). Van Buren did not carry one state, but his 120,000 votes in New York provided Taylor his victory margin in that key state. Taylor's triumph at the polls did not assure a successful Whig administration. In the South, Whig orators had campaigned for Taylor as a southerner and Louisiana slaveholder, a man whom the South could trust, while in the North, Whig politicians portrayed him as a proponent of the Wilmot Proviso. Democratic editors advertised the discrepancy but without apparent effect. By avoiding the slavery-extension issue as a united party, the Whigs, unlike the Democrats, had no solid core of party stalwarts committed to a compromise solution of the territorial question. Any national decision on slavery in the territories could break up the Whig party completely.

Taylor could choose from a host of distinguished Whig leaders in filling his cabinet posts. Henry Clay and Daniel Webster scarcely concealed their resentment toward Taylor's election. Both would attempt to manage the affairs of the nation from their seats in the Senate. Taylor asked his close supporter, John J. Crittenden, to join the cabinet, but Crittenden preferred the governorship of Kentucky. For the State Department, Taylor selected John M. Clayton of Delaware, a noted orator but undistinguished administrator. William M. Meredith, a leading member of the Philadelphia bar, became secretary of the treasury and one of the cabinet's most popular members. Taylor placed the noted Ohio Whig, Thomas Ewing, over the Interior Department. He assigned the little-known George W. Crawford to the War Department. William Ballard Preston of Virginia, secretary of the navy, knew little about ships but much about politics. Jacob Collamer, the postmaster general, was a successful Vermont politician who would become Taylor's chief dispenser of the federal patronage. Reverdy Johnson, a wealthy leader of the Baltimore bar, entered the cabinet as attorney general. Whig editors thought the cabinet moderate and able; at least all of its members appeared to be steadfast Whigs. From the outset Fillmore's role in the new administration was almost nonexistent. He faced opposition not only in the cabinet but also in New York, where the two commanding Whigs, Weed and William H. Seward, fought him successfully for control of the New York patronage.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Elbert B. Smith, The Presidencies of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore (Lawrence, Kans., 1988), is a judicious account devoted specifically to these two presidencies; it is generally complimentary to both. Avery Craven, The Coming of the Civil War (New York, 1942), contains good chapters on the politics and personalities of the Taylor-Fillmore years. Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union , vol. 1 (New York, 1947), covering the years 1847–1852, includes excellent chapters on Taylor, Fillmore, and the Compromise of 1850, as well as on the external challenges in Europe and the Caribbean. Holman Hamilton, Zachary Taylor, vol. 2 (Indianapolis, Ind., 1951), a long and generally sympathetic account of Taylor's presidency, is the standard work on the subject. Brainerd Dyer, Zachary Taylor (Baton Rouge, La., 1946), less detailed than Hamilton's study, notes that Taylor was almost lost in the events of his administration. William Elliot Griffin, Millard Fillmore: Constructive Statesman, Defender of the Constitution, President of the United States (Ithaca, N.Y., 1915), offers perceptive commentary on most aspects of Fillmore's life. The major study of Fillmore's life remains Robert J. Rayback, Millard Fillmore: Biography of a President (Buffalo, N.Y., 1959).

There are excellent biographies of the key congressional actors in the events of the Taylor-Fillmore presidencies. Richard N. Current, Daniel Webster and the Rise of National Conservatism (Boston, 1955), includes an excellent treatment of the debate on the Compromise of 1850. Claude M. Fuess, Daniel Webster , 2 vols. (Boston, 1930), long the standard biography, contains excellent accounts of Webster's role in the Compromise of 1850 and as secretary of state. Carl Schurz, Henry Clay , 2 vols. (Boston, 1899), although old, is still useful for its detailed account of Clay's role in the Compromise; it assigns no role to Douglas. More recent is Glyndon G. Van Deusen, The Life of Henry Clay (Boston, 1937). Charles M. Wiltse treats Calhoun's role in the Compromise generously in John C. Calhoun , vol. 3 (Indianapolis, Ind., 1951). Robert W. Johannsen, Stephen A. Douglas (New York, 1973), is the standard work on Douglas. George Fort Milton, The Eve of Conflict: Stephen A. Douglas and the Needless War (Boston, 1934), an excellent treatment of the events of 1850, focuses on Douglas's contribution.

Holman Hamilton, Prologue to Conflict: The Crisis and Compromise of 1850 (Lexington, Ky., 1964), remains the standard account of the Great Debate of 1850. Edwin C. Rozwenc, ed., The Compromise of 1850 (Boston, 1957), includes excerpts from the major speeches in the Great Debate, three interpretive studies of the Compromise, and several accounts of the year's events. Richard H. Shryock, Georgia and the Union in 1850 (Philadelphia, 1926), focuses on the state's reaction to the Compromise, which was instrumental in determining the general acceptance of the settlement in the South. W. Darrell Over-dyke, The Know-Nothing Party in the South (Gloucester, Mass., 1968), contains a chapter on Fillmore's 1856 campaign as the Know-Nothing candidate.

Recent works include Robert J. Scarry, Millard Fillmore (Jefferson, N.C., 2001).

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: