James A. Garfield and succession Chester A. Arthur - Tragedy and surprise

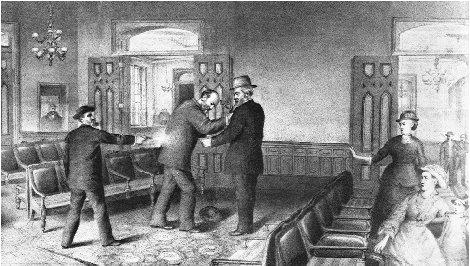

On that date, Charles J. Guiteau shot his way into American history. Guiteau was one of those self-important, self-anointed cranks who haunt the shadowy fringes of power and are merely nuisances until their potential for violence explodes. A failed Oneida colonist, lawyer, religious journalist, and husband, he hung around Republican headquarters in 1880, distributing privately printed copies of a bizarre pro-Republican speech that he believed entitled him to a diplomatic post after Garfield's victory. Brushed off repeatedly at the White House and State Department, he suddenly received what he believed to be a vision from God, wherein he was told that things were not going well with the Republic and that the problem was the new president, who must be removed. Armed with this commandment and a .44-caliber ivory-handled revolver, Guiteau followed Garfield and his traveling party into the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad station and shot him in the back at point-blank range. Then the assassin calmly accepted his arrest, saying, "I am a Stalwart. Arthur is now president of the United States."

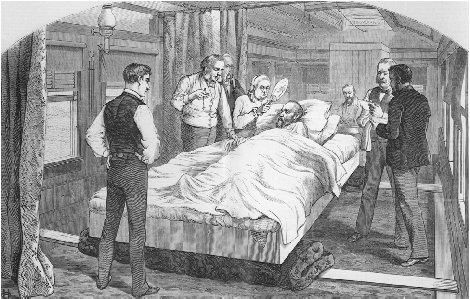

Garfield lingered through a torrid, agonizing summer, wasting away from the effects of blood poisoning caused by the bullet in his spine. It says much about the nature of the federal government in 1881 that there was no problem of carrying on official business during the president's incapacity, which was not to be the case when Woodrow Wilson was fighting for his life in 1919–1920. Congress was in recess, the minimal bureaucracy was virtually shut down in the hot months, and the department heads had no decisions to refer to the president. The basic concern of thoughtful men was what would happen if and when Garfield finally died. The casual way in which the vice presidency was used as a political bargaining chip once again haunted those who believed, with the New York Times , that Arthur's previous career had been a "mess of filth." Even among his familiars, it was later testified, the common reaction was, "Chet Arthur, president of the United States? Good God!"

On 19 September the inevitable calamity came. Garfield died that evening, and at 2:15 A.M. the next day Arthur was sworn in as president in his Manhattan home by a New York State judge. What followed would prove surprising to many people, possibly including Arthur himself.

Arthur's pre-presidential career was not precisely a "mess of filth"—newspaper editors were then prone to hyperbole—but it did not promise much. Arthur was born in 1829 and raised in a Baptist parsonage in Vermont. He escaped from the icy clutch of New England piety by brainpower. He attended Union College and became successively a school-teacher, a lawyer, and a Whig (later Republican) politician, having learned the trade from the master, Thurlow Weed. In 1861 he was made quartermaster general of New York State, thereby earning and keeping the useful title "General," and making important friends among contractors and suppliers. The next year he left the service, gradually became Conkling's chief lieutenant, and in 1871 was rewarded by Grant with the New York collector's job. That empire of fees and jobs allowed him to indulge his Victorian gentlemanly taste for fine food, wines, and cigars; elegant clothes; and leisure. As president, he would keep a ten-to-four workday and a five-day workweek and rarely "did today what he could put off until tomorrow." Some of his indolence may have come from bad health; no one knew at the time that he had Bright's disease. (He was to die of it in 1886, two days after prudently burning all his personal papers.)

As a cultivated and rather aloof man who might have been more at home in London than in Washington, Arthur did not fit the crude image of the party hack. He was, as biographer Thomas Reeves styled him, a "gentleman boss." What the reformers feared was that he would, in effect, turn over the administration of the United States to Roscoe Conkling and the Stalwart machine.

Instead, he scrupulously avoided any taint of jobbery. Conkling got no cabinet seat. (He was offered, but declined, a Supreme Court seat.) Blaine was replaced at the State Department by an experienced and able lawyer and Senate veteran, Frederick T Frelinghuysen of New Jersey. Like several other replacements made by Arthur, he was a Stalwart but one with a clean personal record. The main Half-Breed appointment was that of William E. Chandler, a close ally of Blaine, to the Navy Department. More signifi-cant was something Arthur did not do: he made no attempt to replace Robertson in the New York Customhouse or to open up other patronage jobs for his friends by purging earlier appointees. "He has done

less for us than Garfield, or even Hayes," one Stalwart lamented.

Arthur also inherited one major controversial issue from Garfield in the form of the star-route cases. Along certain star routes, the Post Office Department had the power to award contracts for mail delivery to private express companies rather than setting up its own systems. It was alleged that under Grant some postal officials and contractors had colluded to bilk the government of several millions in padded charges. Garfield's attorney general was supposed to proceed to trial, which was embarrassing, since two of the defendants, Stephen Dorsey and Thomas Brady, had played prominent parts as Republican fund-raisers in the 1880 campaign. Arthur replaced MacVeagh with Benjamin Brewster and told him, "I desire that these people shall be prosecuted with the utmost vigor of the law." The order was carried out, though one trial was invalidated and a second one resulted in acquittal.

As a onetime Conkling follower, Arthur was expected to resist civil service reform stubbornly. Nothing had exceeded the contempt of Conkling himself for the "carpet-knights and man-milliners" of the clean-government camp. But the shock of the assassination made the merit system a proposal whose time had come, as Arthur recognized. In his maiden speech as president, he damned civil service professionalization with the faintest of praise but said he would sign any measure designed to achieve it. Such a bill, the Pendleton Act, did finally cross his desk in January 1883. It was limited in its application, covering only about 11 percent of all federal employees and leaving wide openings for political assessments and payoffs, but it set up the Civil Service Commission, which could later plug those gaps. Arthur not only signed the act but appointed good men to the commission and was praised in their 1885 official report for his "friendly support."

Arthur also seemed willing to modify Stalwart orthodoxy, which decreed support for a high tariff. His second annual message called for reductions in duties on such important items as cotton, iron, steel, sugar, molasses, silk, wool, and woolen goods. Arthur's conversion was in part a product of his discomfort with a treasury surplus, which tariff collections had helped to generate; he believed it was better to have the money out in circulation, helping the economy. It was also a dutiful follow-up to the report of a special tariff commission created by law in 1882 that, although heavily weighted with protectionists, believed many duties could and should be lowered. Congress, while recognizing a growing pressure for modification, proved customarily susceptible to strong lobbying from special-interest groups, and the result was a weak compromise known as the Mongrel Tariff.

In many of his early actions, as president, Arthur gave the impression of someone who, once he got into the office, felt a sudden responsibility to protect and defend its prerogatives. That transformation—which Arthur was not the last to undergo—was most in evidence when he stamped his veto on legislation. Most nineteenth-century presidents shrank from the political barrage that they knew they would have to endure if they said no to a congressional majority. Some still had constitutional qualms about when it was proper to block a bill, but Arthur was on record in favor of an "item veto," which would have let him cancel unpalatable parts of measures that he otherwise approved—something no president has yet gotten—and he did not hesitate to return a porkbarrel internal-improvements bill of 1882 to the Hill, claiming that it was an "extravagant expenditure of public money."

There was a better-known veto in that same year, one firmly anchored to the executive privilege of defending a treaty. In 1868 the United States and China had signed the Burlingame Treaty, giving the nationals of each power the right of free travel and residence in the other. But as wave after wave of Chinese poured into west coast ports to work in the mines and on the railroads, a backlash of already strong anti-Oriental sentiment built up to politically irresistible levels. Racism and economic anxiety reinforced each other as labor unions and politicians—especially on the west coast—demanded that "coolie laborers" be barred from American shores and that Anglo-Saxon civilization be preserved from opium smoking, gambling, and other heathen vices. The Burlingame Treaty was modified by a new one in 1880, giving Congress some powers over Chinese immigration. Thus armed, the lawmakers, in March 1882, enacted a twenty-year ban on the "importation" of Chinese laborers. The same law denied American citizenship to Chinese and imposed special restrictions and requirements on Chinese nationals visiting the United States.

Arthur struck the bill down. He was not entirely heroic; his message indicated that he would accept a ten-year restriction as an "experiment," and part of his motive was fear that the bill would "repel Oriental nations from us and . . . drive their trade and commerce into more friendly hands." He did note that the law, by overriding a treaty, was "a breach of our national faith" and that parts of it were "undemocratic and hostile to the spirit of our institutions." Congress yielded to the president to the extent of passing a fresh exclusion law, this time reducing the term to ten years, and Arthur went along. (The law was consistently renewed, and the hapless Chinese government could only agree to an accomplished fact.) In one other case in 1882, Arthur vetoed a measure setting safety and health standards for incoming immigrant steamers. His grounds were partly technical, but Congress, as in the case of Chinese exclusion, reworked the law to meet his objections before getting his approval.

These were hardly executive triumphs, but they seem somewhat greater when viewed in context. The presidential office had been emasculated under Johnson and disgraced under Grant, and in the disputed election of 1876 it had been further tainted by cheating, haggling, and a secret deal between Republican and Democratic bosses. That Arthur was able to assert any prerogative at all—even negatively, by veto—was a small foretaste of a better future for the presidency.

For the most part, he lacked the initiative for leadership, but in one single area, naval policy, Arthur made at least some difference, through a strong commitment to the modernization and rebuilding of the American fleet. His aim was to correct a weakness in foreign policy—namely, the lack of adequate power to make a drive for expanded commerce.