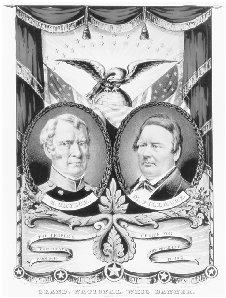

Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore - The california statehood question

Moderates in both houses of Congress hoped to dispose of the slavery issue in California and New Mexico even before Taylor entered the White House. In

January 1848, James Marshall's discovery of gold in the Sacramento Valley set off a rush for the gold-fields. Within weeks thousands of gold seekers moved toward California, some overland by covered wagon, some by ship around South America, and others across the Isthmus of Panama. Convinced that California would soon have more than the sixty thousand inhabitants required for statehood, such House leaders as Clayton and Preston, joined by Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois in the Senate, introduced measures advocating a state government for California. Because any state had the unquestioned right to determine the status of slavery within its borders, state-hood for California seemed a sure remedy for the slavery question there. Southern extremists blocked Douglas in the Senate; Preston's measure remained alive until 27 February 1849, when, overloaded with amendments, the House killed it.

Taylor's inaugural several days later contained no forthright approach to the territorial issue. Democratic editors complained that it shaped no policy at all, keeping the public as much in the dark as it had been at the time of Taylor's election. Southerners suspected that the president's failure to define an antiproviso position meant that he secretly favored a northern solution of the territorial question. Political observers noted, moreover, that most cabinet members leaned toward Free-Soilism.

Privately, Taylor, no less than Clayton and Preston as cabinet members, hoped to avoid a sectional conflict by disposing of the California statehood question as quickly as possible. By December 1849, California's population would approach one hundred thousand. California's loosely organized government, a legacy of Mexican rule, was inadequate to cope with the region's crime and insecurity; indeed, California's citizens were eliminating known criminals by administering justice themselves. Taylor planned to resolve all of California's problems permanently by encouraging immediate statehood. As early as April 1849, Clayton predicted that California "will be admitted—free and Whig!" Taylor dispatched Thomas Butler King, a slaveholding member of Congress from Georgia, to California as his personal agent. King reached the west coast in June and proceeded to argue California's need for statehood. Delegates met in Monterey in September to form a constitution. A third of them were southerners, but their addiction to states' rights prevented them from raising the question of slavery. The constitution, adopted unanimously in October, prohibited slavery for all time. Without waiting for congressional approval, Californians elected state officials and a congressional delegation. Meanwhile, New Mexican leaders also demanded a new government. By the autumn of 1849 the president advocated immediate statehood for both California and New Mexico, revealing at last the antislavery outlook of his administration. During a trip through Pennsylvania in July, Taylor had declared at Mercer, "The people of the North need have no apprehension of the further extension of slavery." Conscious of the growing sectional strife in the nation, Taylor would eliminate the territorial issue by bringing the entire Mexican Cession into the Union as states.