Andrew Jackson

Richard B. Latner

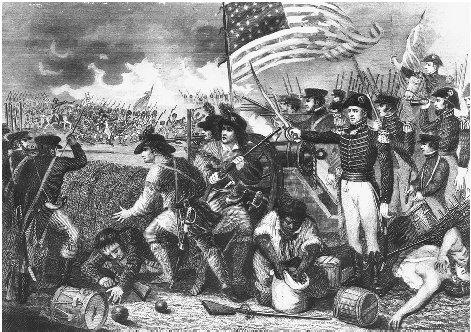

THE familiar labels "The Age of Jackson" and "Jacksonian Democracy" identify Andrew Jackson with the era in which he lived and with the advancement of political democracy. This honor may exaggerate his importance, but it also acknowledges the important truth that Jackson significantly contributed to shaping the American nation and its politics. Just as contemporaneous artists so often depicted him astride his horse overseeing the battlefield, Jackson bestrode some of the key currents of nineteenth-century American political life.

Jackson's presidency began on a sunny, spring-like day, 4 March 1829. Dressed in a simple black suit and without a hat, partly out of respect for his recently deceased wife, Rachel, and partly in keeping with traditions of republican simplicity, Jackson made his way on foot along a thronged Pennsylvania Avenue. From the east portico of the Capitol, he delivered his inaugural address—inaudible except to those close by—in which he promised to be "animated by a proper respect" for the rights of the separate states. He then took the oath of office, placed his Bible to his lips, and made a parting bow to the audience. With great difficulty, he made his way through the crowd, mounted his horse, and headed for the White House and what had been intended as a reception for "ladies and gentlemen."

What next took place has become a part of American political folklore. According to one observer, the White House was inundated "by the rabble mob," which, in its enthusiasm for the new president and the refreshments, almost crushed Jackson to death while making a shambles of the house. Finally, Jackson was extricated from the mob and taken to his temporary quarters at a nearby hotel. "The reign of King 'Mob' seemed triumphant," one cynic scoffed. There was little doubt that Jackson's presidency was going to be different from that of any of his predecessors. Daniel Webster put it best when he predicted that Jackson would bring a "breeze with him. Which way it will blow I cannot tell."

Webster's uncertainty is readily understandable because Jackson was a relative newcomer to national politics. Jackson was born on 15 March 1767, in the Waxhaw settlement, a frontier border area between North and South Carolina, where his early life was marked by misfortune and misadventure. His Scotch-Irish father had joined the tide of immigrants seeking improved economic and political conditions in the New World, only to die after two years, leaving his pregnant wife and two sons. The third son, whom she named Andrew after her late husband, was born just days later. As a young man during the Revolutionary War, Jackson also lost both his brothers and his mother.

Despite these inauspicious beginnings, Jackson received some formal education at local academies and schools, and following the Revolution, he left the Waxhaw community to study law with two prominent members of the North Carolina bar. In the 1780s, after finding little legal work in North Carolina, he migrated to Tennessee, where he showed the good sense to identify himself with the BlountOverton faction, a group of prominent men bound together by politics, land speculation, and, increasingly, financial and banking interests.

The eager, hardworking, and talented young Jackson soon received a host of political rewards. He became a public prosecutor, attorney general for the Mero District, delegate to the Tennessee constitutional convention, a member of Congress, a United States senator, and a judge of the Superior Court of Tennessee. By the year 1800, he was the leader of the Western branch of the Blount-Overton faction.

Military positions also came Jackson's way, and he gradually advanced from his appointment as judge advocate for the Davidson County militia in 1792 to be elected major general of the Tennessee militia a decade later. At the same time, he accumulated significant amounts of property, establishing himself as a member of the Tennessee elite by purchasing a plantation, first at Hunter's Hill and then, in 1804, at the Hermitage, near Nashville.

Jackson's enormous military success during the War of 1812, culminating in the Battle of New Orleans, made him a national hero, and during the winter of 1821–1822, political friends placed his name before the country as a presidential candidate in the election of 1824. His first presidential bid fell short, for in a four-way contest, Jackson won a plurality of the popular vote but failed to receive an electoral majority. The decision rested with the House of Representatives, and John Quincy Adams emerged victorious after receiving the support of Henry Clay. When Adams appointed Clay as his secretary of state and heir apparent, Jacksonians alleged a "corrupt bargain." Jackson himself always believed that the will of the people had been corruptly overturned, and he denounced Clay as "the Judas of the West." Although it is unlikely that Adams and Clay actually made a secret deal, Jackson had a telling point in that Clay's action deprived the most popular candidate of the presidency. The incident strengthened Jackson's conviction that a republic should be based on the democratic principle of majority, not elite, rule.

Four years later, Old Hickory was vindicated. In the election of 1828, he received about 56 percent of the popular vote and carried virtually every electoral vote south of the Potomac River and west of New Jersey. Yet Jackson's victory was the product of a diverse coalition of groups rather than of a coherent political party. In addition to the original Jackson men from the campaign of 1824, there were the followers of New York's Martin Van Buren and Jackson's vice president, South Carolina's John C. Calhoun; former Federalists; and groups of "relief men," who during the Panic of 1819 had bucked the established political interests by advocating reforms to help indebted farmers and artisans.

Further, there were few clear-cut issues dividing the candidates. Instead, popular attention was captured by a host of scurrilous charges that dragged the contest down to the level of mud-slinging. Rachel, for example, was accused of bigamy in marrying Jackson while she was legally attached to another man. Jackson men, in addition to harping on the corrupt-bargain charge, accused Adams of pimping for the czar while he was minister to Russia.

Nevertheless, there were signs even in that campaign of Jackson's future course. The Jackson men

of 1828 already displayed elements of the political organization that would emerge during his presidency. Significantly, his followers showed themselves more adept than the opposition at appealing to the people and organizing grassroots sentiment. The center of the Jackson campaign was the Nashville Central Committee, whose key members were Jackson's earliest and closest associates in Tennessee politics, such as John Eaton, John Overton, and William B. Lewis. This committee linked together the numerous state and local Jackson organizations and worked closely with political leaders in Washington.

The Jackson committees encouraged a more popular and democratic style of politics by organizing rallies, parades, and militia musters; helping to sustain Jackson newspapers; and encouraging voters to cast their ballots for Jackson on election day. This was the first election in which gimmicks such as campaign songs, jokes, and cartoons were extensively used to arouse popular enthusiasm. Years before, Jackson's soldiers had given him the nickname Old Hickory to signify both his toughness and their affection for him. During the 1828 campaign, his followers ceremoniously planted hickory trees in village and town squares, and sported hickory canes and hats with hickory leaves. Hickory poles, symbolically connecting Jackson to the liberty poles of the revolutionary era, were erected "in every village, as well as upon the corners of many city streets." Jackson himself, while avoiding overt electioneering displays, carefully supervised this political activity.

The election of 1828 also hinted at Jackson's future program. Until recently, Jackson was rarely considered a man with any coherent political views. Most accounts treated him as a confused, opportunistic, and inconsistent politician. Jackson, to be sure, had no formal political philosophy, but he adhered to certain underlying values and ideas with a degree of consistency throughout his long political career.

Jackson's philosophy owed much to the teachings of Thomas Jefferson and to the tradition of republican liberty of the revolutionary generation. One of the unique products of the American Revolution was the new and distinctive definition it gave to classical and Renaissance traditions of republicanism. Revolutionary thinkers taught that liberty was always jeopardized by excessive power and that a proper balance and limitation of governmental powers was essential to assure freedom. In addition, this ideology of republicanism also emphasized that the character and spirit of the people—what was called public virtue—were fundamental to maintaining a free society. A virtuous citizenry was necessary to liberty, and whatever corrupted the people thereby corrupted their institutions. Rooted in an agrarian, premodern society, traditional republican thought warned of the competing dangers inherent in an expansive market economy, such as stockjobbing, paper credit, funded debts, powerful moneyed interests, a swollen bureaucracy, and extreme inequality of condition.

During the nineteenth century, Americans accommodated republicanism's precapitalistic bias to the dramatic changes in transportation, communication, and economic activity that have been called the Market Revolution. Especially after the War of 1812, Americans acknowledged that it was no longer possible or even desirable to maintain a rigid agrarian social order. They increasingly accepted as beneficial certain material and moral aspects of a developing economy. Economic ambition, for example, need not breed only luxury and corruption; it could also promote industriousness, frugality, and other republican virtues. Nevertheless, many Americans continued to harbor anxieties that the emerging world of commerce, banking, and manufacturing endangered the conditions essential to maintain liberty. In short, the language of republicanism remained potent throughout the Jacksonian era, but its diagnosis of the condition of the American republic was subject to different interpretations.

These ideas left their mark on Jackson. It was evident in his highly moralistic tone; his agrarian sympathies; his devotion to the principles of states' rights and limited government; and his fear that speculation, moneyed interests, and human greed would corrupt his country's republican character and institutions. At the same time, he was not a rigid traditionalist. He accepted economic progress, a permanent and expanding Union with sovereign authority, and democratic politics. His philosophy, therefore, brought together the not entirely compatible ideals of economic progress, political democracy, and traditional republicanism.

In the campaign of 1828, Jackson's sentiments distinguished him from Adams. While Adams viewed an active and positive government as promoting liberty, Jackson preferred to limit governmental power and return to the path of Jeffersonian purity. The comparison was by no means perfect. Jackson intended no states' rights crusade, and he dissatisfied some idealists, particularly in the South, by endorsing some tariff protection and the distribution of any surplus revenue back to the states. Yet it was evident that, compared to his opponent, Jackson would qualify federal activity. He considered his victory a moral mandate to restore "the real principles of the constitution as understood when it was first adopted, and practiced upon in 1798 and 1800." His specific program was to become clear only as his presidency unfolded.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A short, highly interpretive biography of Andrew Jackson emphasizing his psychological impulses is James C. Curtis, Andrew Jackson and the Search for Vindication (Boston, 1976). The best modern biography of Jackson is a three-volume work by Robert V. Remini: Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767–1821 (New York, 1977), Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832 (New York, 1981), and Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (New York, 1984). On the influence of republican ideology on Jackson's presidency, consult Richard B. Latner, The Presidency of Andrew Jackson: White House Politics, 1829–1837 (Athens, Ga., 1979), and Harry L. Watson, Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian America (New York, 1990). For a different view of Jackson's presidency, see Donald B. Cole, The Presidency of Andrew Jackson (Lawrence, Kans., 1993). Drew R. McCoy, The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1980), explains the complexity of republican thinking in an earlier era.

Historians have long debated the meaning of Jacksonian politics. Marvin Meyers, The Jacksonian Persuasion: Politics and Belief (Stanford, Calif., 1957), is in many respects the most successful interpretation of Jacksonianism. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Age of Jackson (Boston, 1945), still offers a vivid portrait of the democratic qualities of Jacksonian politics. Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York, 1991), is a learned and comprehensive account of Jacksonian America's confrontation with the market revolution.

On the political issues of Jackson's presidency, Matthew A. Crenson, The Federal Machine: Beginnings of Bureaucracy in Jacksonian America (Baltimore, 1975), places Jackson's administrative actions in a broad social framework. Daniel Feller, The Public Lands in Jacksonian Politics (Madison, Wis., 1984), thoroughly examines the political and sectional dimensions of this issue. On Indian policy, Michael Paul Rogin, Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian (New York, 1975), is both insightful and controversial in its psychological orientation. Ronald N. Satz, American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era (Lincoln, Nebr., 1974), is an excellent analysis of the many aspects of Indian removal. Anthony F. C. Wallace, The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians (New York, 1993), provides a brief and useful introduction to the process of Indian removal.

Jackson's banking and financial policy is critically examined in Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (Princeton, N.J., 1957). John M. McFaul, The Politics of Jacksonian Finance (Ithaca, N.Y., 1972), is more favorable to Jackson, while Peter Temin, The Jacksonian Economy (New York, 1969), places economic events in an international and theoretical context. William W. Freehling, Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816–1836 (New York, 1966), is a model historical study of this crisis. Richard E. Ellis's excellent study, The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States' Rights, and the Nullification Crisis (New York, 1987), argues the strength of nullification. Daniel Walker Howe, The Political Culture of the American Whigs (Chicago, 1979), perceptively explores the values and thinking of the Whig opposition, while Merrill D. Peterson, The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun (New York, 1987), contains a wealth of information about Jackson's leading opponents.

Two essays that argue that Jackson and the Democratic party tilted toward the South and slavery are Richard H. Brown, "The Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism," in South Atlantic Quarterly 65 (1966), and Leonard L. Richards, "The Jacksonians and Slavery," in Lewis Perry and Michael Fellman, eds., Antislavery Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Abolitionists (Baton Rouge, La., 1979). Robert V. Remini, The Legacy of Andrew Jackson: Essays on Democracy, Indian Removal, and Slavery (Baton Rouge, La., 1988), provides a useful correction to this view. Russel B. Nye, Fettered Freedom: Civil Liberties and the Slavery Controversy, 1830–1860, rev. ed. (East Lansing, Mich., 1964), remains an excellent study of the mail and petition controversies as well as other slavery-related issues. William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854 (New York, 1990), contains numerous insights about slavery and politics. Two other studies of southern locales show how Jacksonian politics operated on a smaller scale: J. Mills Thornton III, Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800–1860 (Baton Rouge, La., 1978), and Harry L. Watson, Jacksonian Politics and Community Conflict: The Emergence of the Second American Party System in Cumberland County, North Carolina (Baton Rouge, La., 1981).

Jackson's foreign policy receives careful attention in John M. Belohlavek, "Let the Eagle Soar!": The Foreign Policy of Andrew Jackson (Lincoln, Nebr., 1985). Also useful are William H. Goetzmann, When the Eagle Screamed: The Romantic Horizon in American Diplomacy, 1800–1860 (New York, 1966), and Paul A. Varg, United States Foreign Relations: 1820–1860 (East Lansing, Mich., 1979).

Recent works include Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and His Indian Wars (New York, 2001).

Further reference sources can be found in Robert V. Remini and Robert O. Rupp, Andrew Jackson: A Bibliography (Westport, Conn., 1991).

:)

thank you so much!

I wish it was a little better organized, but all the information's here so I guess I can't complain hahaha

this book "A people's History of The United States. He claims that if you look through

High school history textbooks you will find Jackson frontiersman, soldier, democrat, man

of the people - not Jackson the slaveholder, land speculator, executioner of dissident

soldiers, exterminator of Indians. I personally don't know if this is true about the text books in High schools today. DO you?