John Quincy Adams - Election of 1824

In the judgment of many historians, Adams' presidency was doomed to failure because of the manner in which he gained the high office. Adams never lived down the charge by his leading opponent that he had secured the necessary majority in the House only by agreeing to a "corrupt bargain," by which Adams allegedly rewarded Henry Clay with the post of secretary of state—then the stepping stone to the presidency—in return for Clay's intriguing and manipulating in the House to switch votes to Adams.

The fascinating presidential election of 1824 was a turning point in many ways. It followed a succession of three two-term presidents, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe—the famous "Virginia Dynasty"—each of whom was identified with Jefferson's Republican party. Monroe had run unopposed in 1820, for the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and John Adams had finally given up the ghost, unable to shake off the popular belief that, in opposing as it had the War of 1812, it had skirted perilously close to treason.

Even before the disintegration of Federalism, the Republicans had the presidential field pretty much to themselves, as party members in Congress would meet in closed caucus to name the candidate for the forthcoming presidential election. As Monroe's second term approached its end, the Republican congressional caucus by an almost unanimous vote recommended William H. Crawford of Georgia, secretary of the treasury in Monroe's cabinet, as its candidate for president. According to Martin Van Buren, the political genius who controlled Republican politics in New York State, acceptance of the caucus' choice for office was an "article of faith" or fundamental tenet of the Republican party. Not in 1824. Van Buren and not too many others dutifully threw their energies into the election of Crawford. But a number of other men, Republicans all, sensing that the caucus selection could this time be successfully opposed, threw their own hats into the ring. John Quincy Adams was one of this ambitious quartet.

By 1824, Crawford's rivals no doubt agreed with the newly skeptical attitude toward caucus selection that was expressed by Adams in his diary entry for 25 January 1824. He had come to believe that "a majority of the whole people of the United States, and a majority of the States [were] utterly averse to a nomination by Congressional caucus, thinking it adverse to the spirit of the Constitution and tending to corruption." Adams was no doubt sincere in his insistence that since he agreed with this sentiment, he could not accept a caucus nomination for the presidency, but he would have sounded more convincing had he had a realistic chance of securing such nomination. But he must have known that there was no such chance. Motivated as he was by soaring ambition, this pillar of rectitude sought to convince himself that he was breaking with tradition only for the loftiest and most principled of reasons. The other contestants simply saw their chance and took it.

Adams' several rivals constituted one of the most impressive constellations of political luminaries that ever vied for the presidency in any single election. In addition to the estimable Crawford, the group included John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, the brilliant Yale-educated nationalist who served as secretary of war under Monroe; Henry Clay of Kentucky, the master politician who had been the chief architect of the Missouri Compromise; and General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, a man of slight political achievement, little education, and notorious temper, but widely admired for his exploits as an Indian fighter and above all for his stunning victory in 1815 over the British at New Orleans. Withdrawing from the race when it became clear that he had no real chance to win, Calhoun and his backers settled for second place under the presidency of either of the two leading candidates—Adams, the only northerner in the competition, and Jackson, the darling of the South and West.

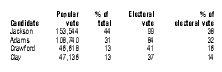

The election returns make clear how decisively the latter two candidates outdistanced Crawford and Clay. The tallies were as follows:

| Candidate | Popular vote | % of total | Electoral vote | % of electoral vote |

| Jackson | 153,544 | 44 | 99 | 38 |

| Adams | 108,740 | 31 | 84 | 32 |

| Crawford | 46,618 | 13 | 41 | 16 |

| Clay | 47,136 | 13 | 37 | 14 |

Since no candidate had won the required majority of electoral votes, the choice was turned over to the House of Representatives, in accord with Article II of the Constitution. Since, by Article XII, only the top three vote-getters qualify in such a circumstance, Clay's name was dropped from the list presented to the lower house. Since Crawford was known to have become physically incapacitated and unable therefore to perform the duties of the high office, there was very little chance that many in Congress would join the diehards who appeared ready to stand by Crawford, near-dead or fully alive. In his diary entry for 9 February 1825, Adams wrote, "May the blessing of God rest upon the event of this day," for earlier that day, Adams had been selected by the approving vote of thirteen states, with Jackson supported by seven states and Crawford by four.

Three weeks and two days later, Adams reported that he had suffered through two sleepless nights prior to inauguration day. His excitement and unease were induced not only by the fact that he was about to assume the great burden of the presidency but by the vilification that the Jacksonians had heaped on him for what they claimed were the sordid means by which he had won the election to the office in Congress.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: