James Monroe

Harry Ammon

INAUGURATION day, 4 March 1817, was one of those rare late winter days in Washington with more than a hint of spring—sunny and balmy. Throughout the morning a steady stream of citizens hastened along the dusty, rutted streets toward the temporary congressional quarters in a frame structure across from the burned-out Capitol. The crowd, largely composed of residents of the city, included visitors from as far away as New York who had taken advantage of the cheaper rapid transportation offered by the newly introduced steamboats. By noon a crowd estimated at eight thousand, the largest ever assembled in Washington, had gathered.

The circumstances that occasioned an outdoor ceremony were entirely fortuitous. Usually inaugurations were held in the House chamber, but the refusal of the representatives to let the senators bring with them their new red upholstered armchairs had culminated in a deadlock broken only by deciding to move the ceremony outdoors. The managers were so distracted by this dispute that they forgot to invite the diplomatic corps, which was conspicuously absent. President-elect James Monroe and his vice president, Daniel D. Tompkins, arrived shortly before noon, escorted by a troop of volunteer cavalry. After being greeted by retiring President James Madison, the party entered the House chamber, where the vice president was sworn in, before returning to the outdoor platform. Monroe was then administered the oath of office by Chief Justice John Marshall, a friend of his youth but since alienated by political differences.

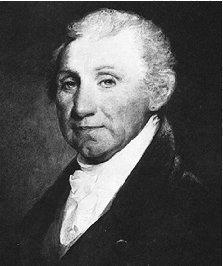

The new president, who stepped forth to deliver his inaugural address, was a familiar figure to Washingtonians, who were accustomed to seeing him go about the city clad in the smallclothes of an earlier age—a black coat, black knee breeches, and black silk stockings. On ceremonial occasions he often wore a blue coat and buff knee breeches, an outfit reminiscent of Revolutionary War uniforms. Now in his fifty-ninth year, Monroe was erect in bearing, robust and vigorous in manner. His hair (worn long and tied behind with a black ribbon) had grayed, and his face had become deeply lined during the recent war. Nearly six feet tall, with dignified and formal manners, he was an impressive figure but by no means handsome—his face was plain, the nose large though regular. His wide-set gray eyes were his most striking feature, exhibiting a generosity of spirit confirmed by the warmth of his smile. Never arousing the same passionate devotion as Jefferson, Monroe was admired for his heroism during the Revolution and for his long service to the nation.

In his inaugural address—described by one auditor as of a "plain homespun character"—Monroe spoke of the renewed sense of national unity apparent after the difficulties of the war years. Espousing a course of moderate nationalism, he recommended the continued protection of domestic manufactures. He also stressed the need for the construction of roads and canals to facilitate the movement of commerce, but failed to clarify his position on the constitutionality of federally funded internal improvements. He devoted the lengthiest portion of his message to a project in which he took a personal interest—the need to improve the defenses of the nation by maintaining a larger peacetime army and by the construction of a chain of coastal fortifications to avert the danger of future invasion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Stanislaus Murray Hamilton, ed., Writings of James Monroe , 7 vols. (New York, 1898–1903), the only printed edition, is of limited value and has now been fully supplanted by microfilm editions of all major collections of Monroe's papers. Harry Ammon, James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity (New York, 1971; rev. ed., Charlottesville, Va., 1990), is a full-scale biography based on primary materials. George Dangerfield, Era of Good Feelings (New York, 1952), is a limited study depicting Monroe as a dullard and time-serving politician. Noble E. Cunningham, Jr., The Presidency of James Monroe (Lawrence, Kans., 1996), contains the latest scholarship on the last of the Virginia presidents.

Leonard D. White, The Jeffersonians: A Study in Administrative History, 1801–1829 (New York, 1951), superbly details the operation and organization of federal administration under Monroe. Norman K. Risjord, The Old Republicans: Southern Conservatism in the Age of Jefferson (New York, 1965), is a scholarly account of the opposition to Monroe's policies from within his own party. Charles M. Wiltse, John C. Calhoun , 3 vols. (New York, 1944–1951), includes an extensive account of Monroe's Indian policy based on original sources.

Alexander DeConde, Entangling Alliance: Politics and Diplomacy Under George Washington (Westport, Conn., 1974), is essential for understanding Monroe's mission to France. Bradford Perkins, Castlereagh and Adams: England and the United States, 1812–1823 (Berkeley, Calif., 1964), depicts the close working relationship between Monroe and his secretary of state. Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy (New York, 1949), is a definitive study of Monroe's foreign policy. Hugh G. Soulsby, The Right of Search and the Slave Trade in Anglo-American Relations, 1814–1862 (Baltimore, 1933), is a basic study of a major issue confronting Monroe's presidency.

Dexter Perkins, The Monroe Doctrine, 1823–1826 (Cambridge, Mass., 1927), is still the definitive monograph about the origins of the doctrine. Ernest R. May, The Making of the Monroe Doctrine (Cambridge, Mass., 1975), is a revisionist study arguing that it was issued solely to influence the outcome of the presidential election of 1824. Arthur P. Whitaker, The United States and the Independence of Latin America, 1800–1830 (Baltimore, 1941), is indispensible for understanding Monroe's Latin American policy.

Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time , 6 vols. (New York, 1948–1981), is a splendid biography with a full account of the impact on American politics of Jefferson and Monroe's lifelong friendship. Irving Brant, James Madison , 6 vols. (Indianapolis, Ind., 1941–1961), touches extensively on his relationship with Monroe. Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767–1821 (New York, 1977), Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832 (New York, 1981), and Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (New York, 1984) are scholarly pro-Jackson works highly critical of Monroe's treatment of Jackson; Remini's Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (New York, 1959) is a fascinating account of Van Buren's reorganization of the Democratic party in its depiction of Monroe as an apostate. Lucius Wilmerding, Jr., James Monroe, Public Claimant (New Brunswick, N.J., 1960), contends that Monroe's postretirement claims for expenses as a diplomat were unjustified.

Harry Ammon, ed., James Monroe: A Bibliography (Westport, Conn., 1991), is a comprehensive annotated bibliography.

Thanks, maggie